Kansas City’s public education landscape is changing. Changing teacher demographics, and a shifting employment landscape, are important parts of this larger story.

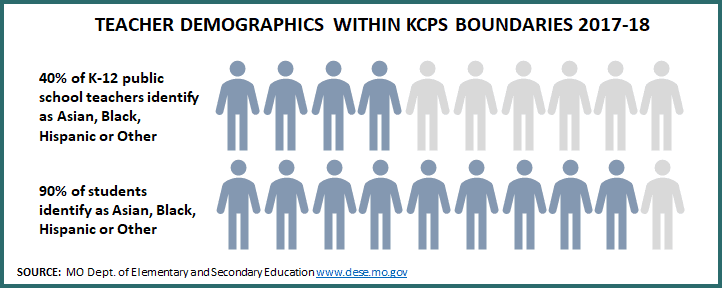

My last post looked at teacher demographic data within KCPS boundaries during the 2017-18 school year. I started with one year of data because it’s important to have a baseline, and to know what our teaching staff looks like today.

But looking at a single year of data in isolation doesn’t tell us the whole story. What’s the big picture?

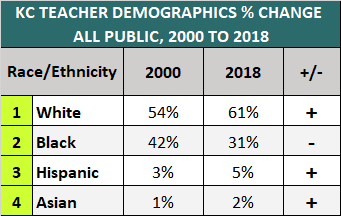

Overall, an increasing percentage of our teacher workforce is White. In both KCPS and the charter sector, the percentage of White teachers has grown over time. Representation of Asian and Hispanic teachers has increased marginally. The percentage of Black teachers has steadily decreased.

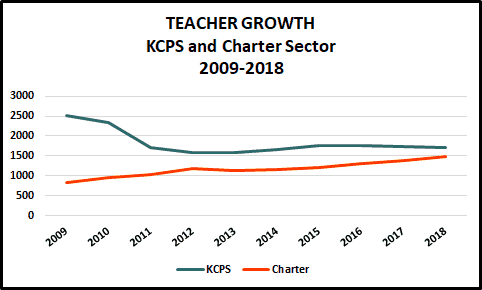

This analysis holds true for both KCPS and the charter sector – though under somewhat different conditions: overall contraction in the KCPS teacher labor pool, and overall growth in the charter sector.

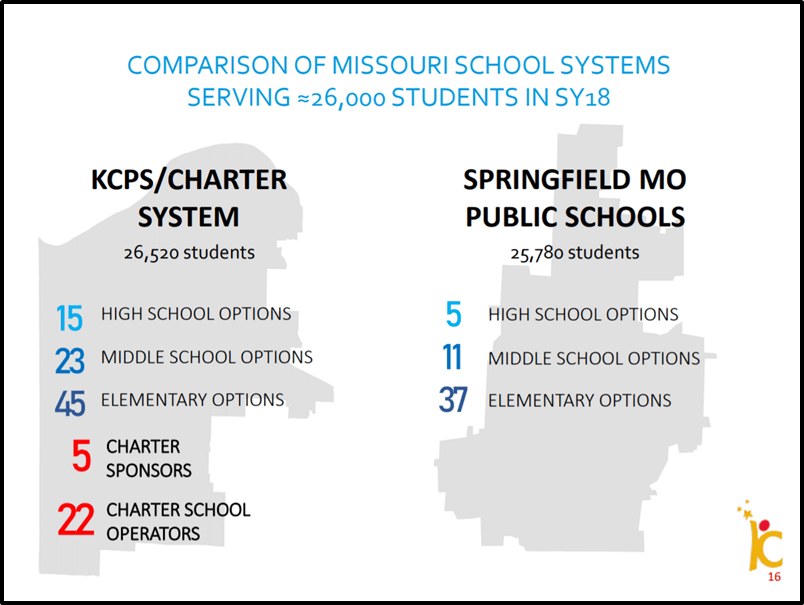

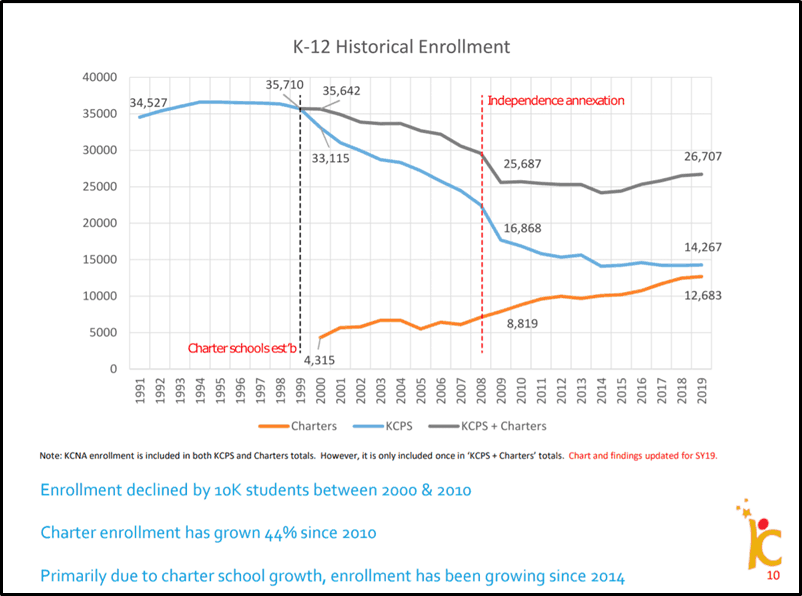

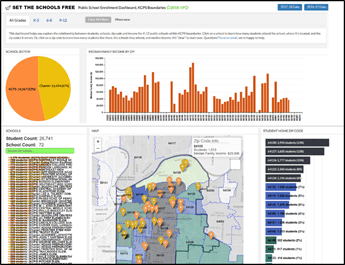

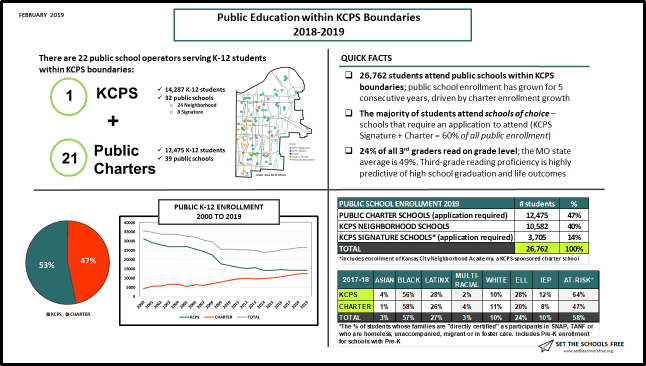

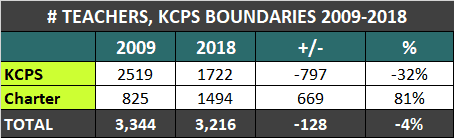

KCPS remains the single largest employer of teachers. But, similar to K-12 student enrollment, we’re quickly approaching a teacher “tipping point”: in 2018, 46% of all public school teachers within KCPS boundaries taught in public charter schools.

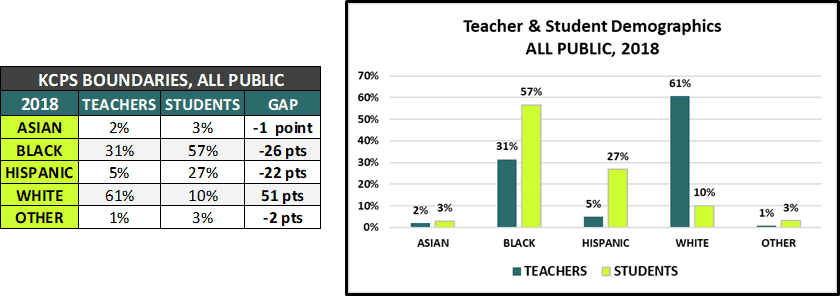

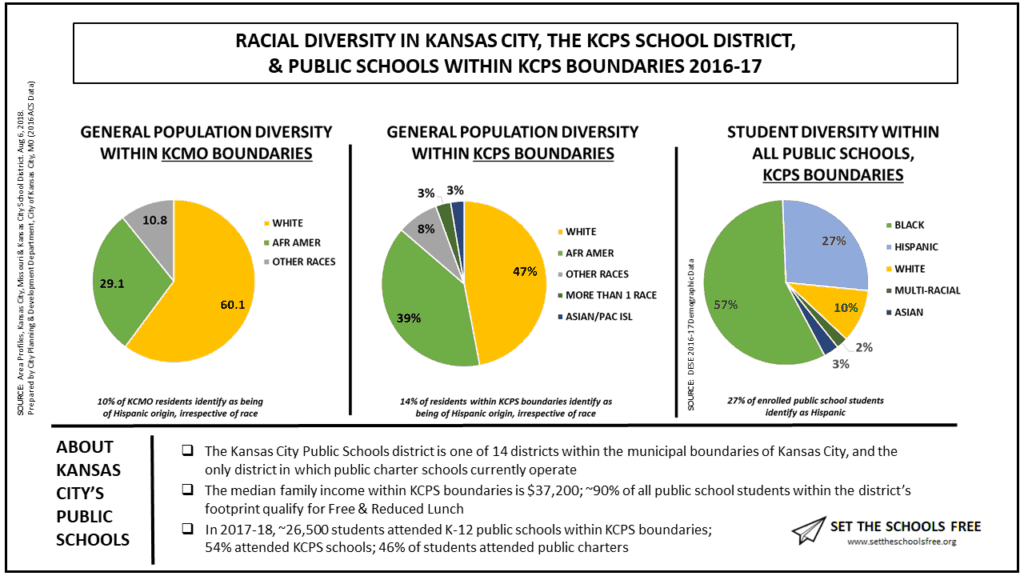

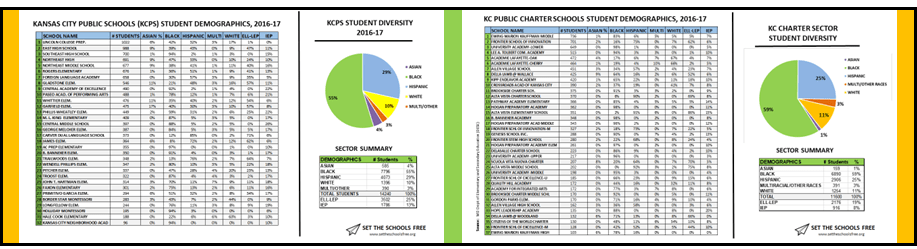

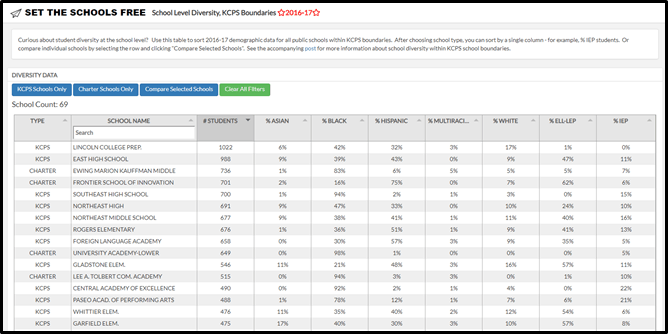

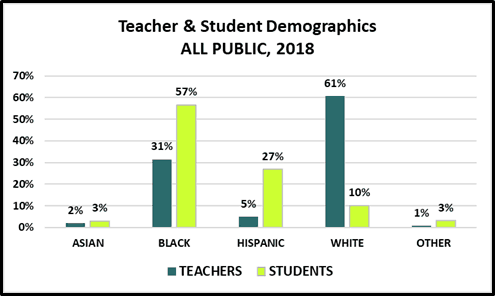

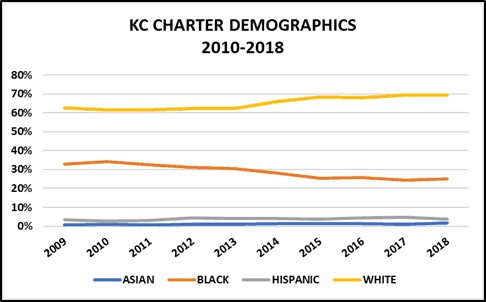

A quick look at student demographics

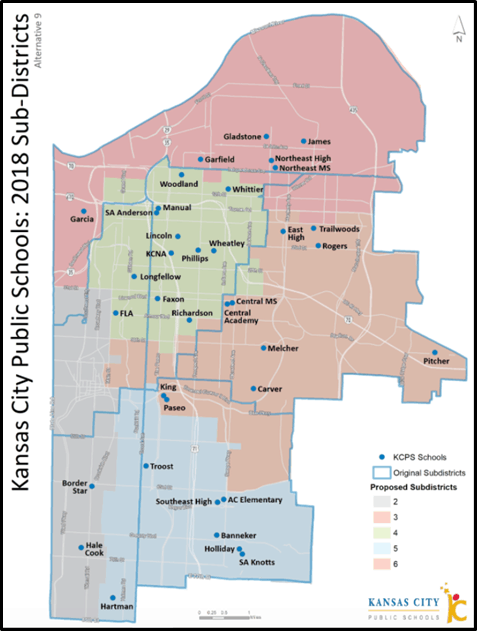

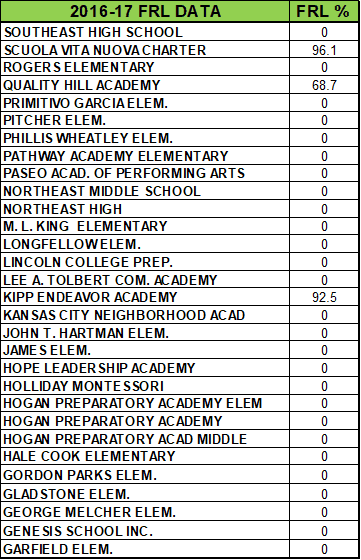

It’s important to understand teacher demographics in the context of the student population our schools serve. The next few sections break out the trend data in three ways: 1) ALL public (KCPS + Charter), 2) KCPS, and 3) Charter. To keep things simple, I don’t go into student demographics in detail – you can find a detailed analysis of student demographics over time here. But the broad 2009-2018 student trends are:

- Asian student enrollment: Slight growth in both KCPS and the charter sector

- Black student enrollment: Trending down in KCPS, growing steadily in charter sector (net loss overall)

- Hispanic student enrollment: Trending up in both KCPS and charters (Hispanic students are the fastest growing demographic in our district)

- White student enrollment: Slightly down in KCPS; trending up in the charter sector

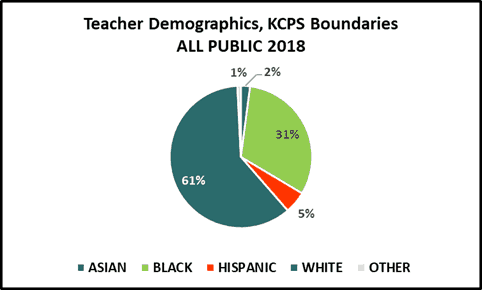

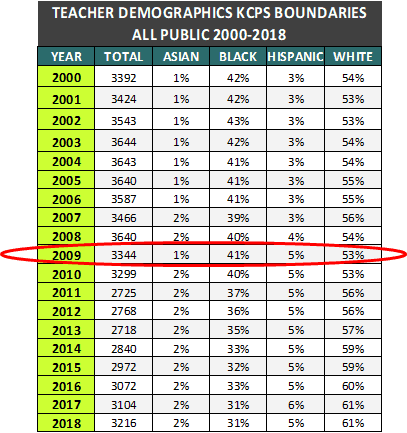

Teacher demographics, ALL public

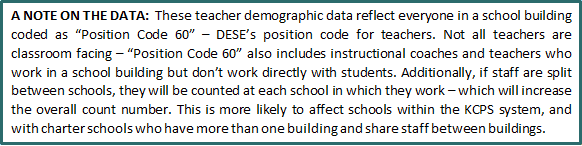

In 2000, a majority of public school teachers within KCPS boundaries – 54% – self-identified as white. Black teachers, at 42%, made up the second largest demographic group. Asian and Hispanic teachers made up 1% and 3%, respectively.

This representation holds more or less steady until 2009, when we begin to see a demographic shift: the percentage of Black teachers starts to decrease, and the percentage of White teachers begins to grow. Overall there is slight growth in the percentage of Hispanic and Asian teachers during this period.

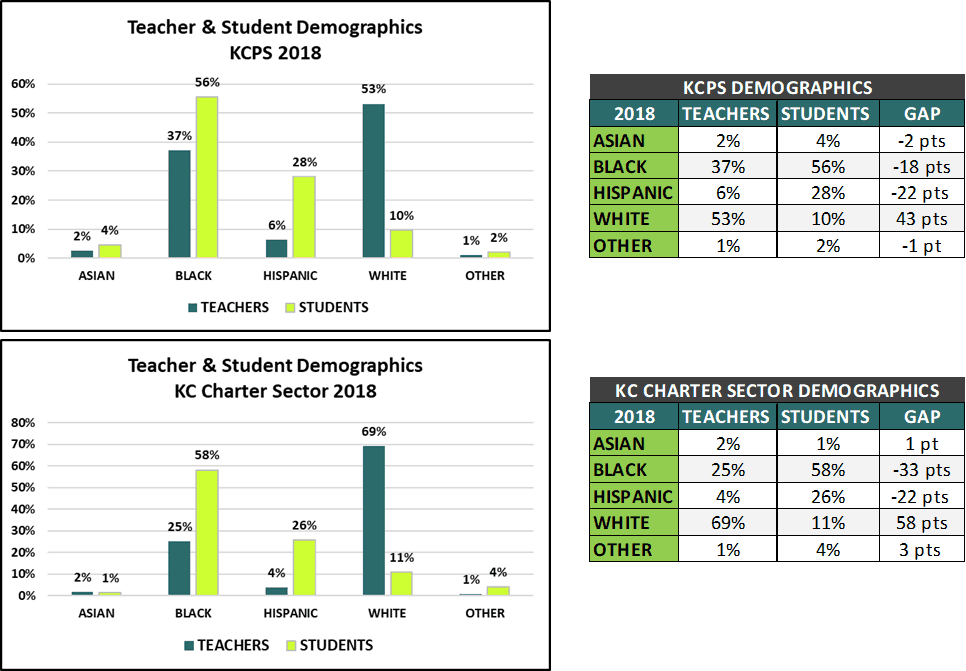

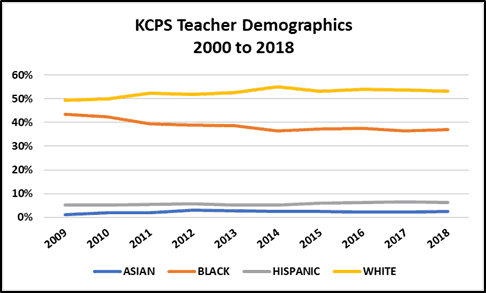

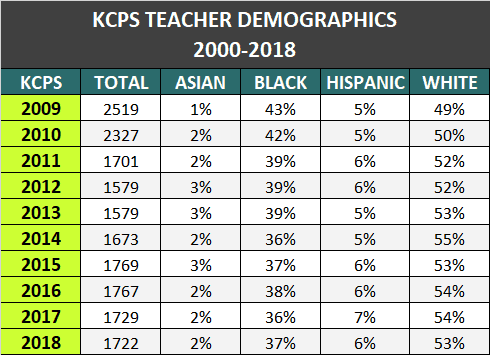

KCPS teacher demographics: 2009-2018

In 2000, 31,327 K-12 students attended KCPS schools. By 2018, enrollment was just 14,221 students – a 55% drop.

The effects of this decline were felt most acutely in 2010, when 26 schools closed under then-Superintendent John Covington’s Right-Sizing plan. Fewer students, and fewer schools, also meant fewer KCPS teachers: between 2009 and 2013, the number of KCPS teachers decreased by more than one-third, from 2519 teachers to 1579.

It’s at this point that the demographics of the KCPS teacher workforce begin to change: the percentage of White teachers starts growing – and Black teacher representation begins to decline in parallel.

Asian and Hispanic representation during this period is more or less flat.

After 2013, as student enrollment begins to steady, the number of KCPS teachers begins to rebound, slowly. But the percentage of Black teachers continues to decrease – by 2018, the number of Black KCPS teachers has dropped by over 40%.

The percentage of Asian and Hispanic teachers remains fairly flat.

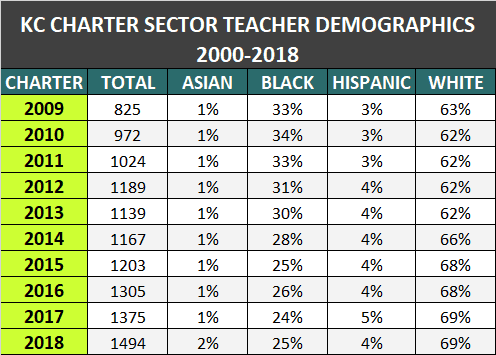

Charter Sector teacher demographics 2009-2018

From 2009 to 2018 student enrollment in Kansas City charter schools grew – and with it, the number of teachers employed by charter schools.

K-12 charter enrollment grew more than 50% during this period, from 7,904 in 2009 to 12,305 in 2018. The number of charter school teachers teachers grew by 81%, from 825 to 1494.

But the same overall trends we saw in KCPS apply to the charter sector as well, except this time in an overall context of sector growth.

The absolute number of Black teachers increases – there are more Black teachers in charter schools in 2018 (374) than there were in 2009 (272). But this increase doesn’t keep up with overall teacher growth in the sector, resulting in an overall percentage decline: in 2009 one of three charter school teachers was Black; in 2018, only one of four teachers is.

In 2018, only 54 charter school teachers (4%) self-identified as Hispanic; 24 teachers (2%) identified as Asian.

Putting the pieces together

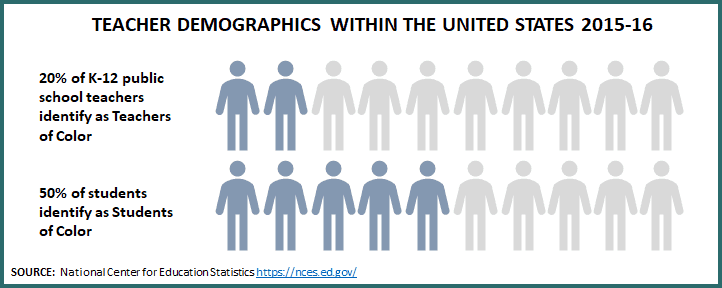

As I wrote in Teacher Demographics Part I, an ever-growing body of research shows that students benefit – socially, emotionally, and academically – from having teachers of their same race and gender.

Within KCPS boundaries, our teaching workforce is becoming increasingly White. The driving force behind this decrease in diversity is the loss of Black teachers in KCPS. This trend continued even after KCPS enrollment steadied, and KCPS teacher employment began to rebound.

As charter enrollment increased during this same period, the number of Black teachers in charter schools grew with it. But it didn’t keep up with overall teacher growth – resulting in a decrease in the percentage of Black teachers.

Finally, the growth of Asian and Hispanic teachers is slight, though important. But when you consider that Hispanic students are the fastest-growing student population in our district you realize the scope of the challenge our schools face in serving this population well, whether from a cultural or language perspective. In 2018 there were more than 7,200 Hispanic students in our public schools – and just 162 Hispanic teachers, both KCPS and charter combined.

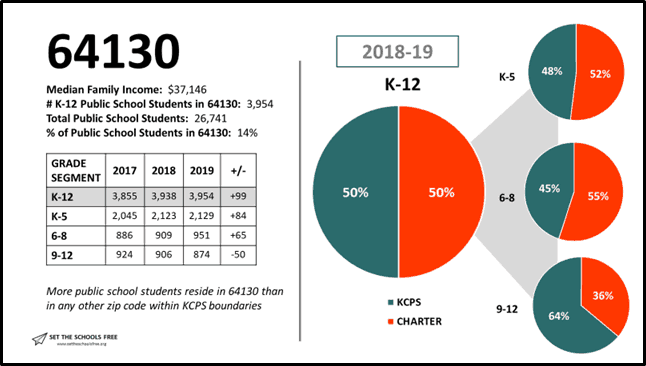

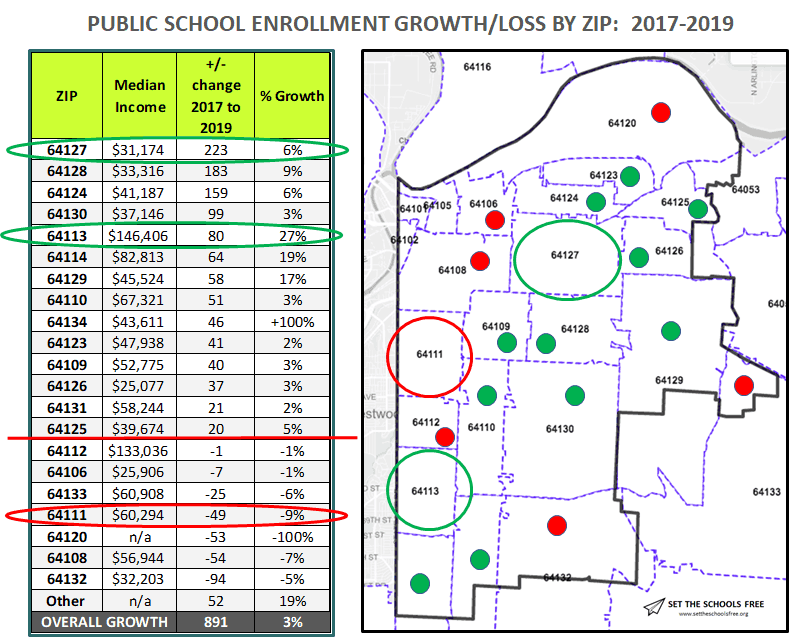

I’ve written previously about changing student demographics within KCPS boundaries – you can find this analysis here. You can find a more comprehensive analysis of public school enrollment through 2018 here.

Closing thoughts

The point of this post, and of Set the Schools Free more broadly, is to create awareness of the facts, so we can have more thoughtful and solutions-oriented conversations about the challenges our public schools, both KCPS and charter, face. Building and sustaining a diverse teacher pipeline is one of these challenges.

If you want to learn more about why a diverse teacher pipeline is important, and what that pipeline looks like at the national level, you may find these resources helpful: Why we need a diverse teacher workforce, from the Phi Beta Kappan; The Washington Post: America’s schools are more diverse than ever. But it’s teachers are still mostly white; Diversifying the Classroom: Examining the Teacher Pipeline, from The Urban Institute; and Teacher Diversity, from the National Council for Teacher Quality.

In my last post I included a list of organizations working locally to recruit, develop and retain teachers of color. This list has grown. It includes: Kansas City Plus+, The Kansas City Teacher Residency, The LatinX Education Collaborative, The Literacy Lab, Teach for America KC, the UMKC Institute for Urban Education, AmplifyKC, Brothers Liberating our Communities (The BLOC) and Elements of Education KC.

As always, I welcome your comments, questions, and feedback.