The idea of school-level accountability is a powerful one. The lessons from Banneker’s closure are important as Kansas City’s charter sector grows, and as KCPS moves more intentionally into charter sponsorship.

Benjamin Banneker Charter Academy for Technology, a Kansas City charter school, closed over the summer. Banneker was a K-8 school that served 320 students. It was one of the original 15 charter schools that opened in Fall 1999, the first year charters operated in Kansas City – and the 10th KC charter school to close.

What can we learn from Banneker’s closure?

First, some background. Charters are publicly-funded schools that operate independently of traditional school districts.

In charter schools, decisions about time, staffing, money and curriculum are made at the school level. This is what’s known as school autonomy.

In exchange for autonomy, charter schools are held accountable for academic performance. Performance expectations are laid out in a contract (a charter) and are evaluated regularly by the school’s accountability agent (its sponsor). If a school doesn’t fulfill the terms of its contract it’s supposed to close.

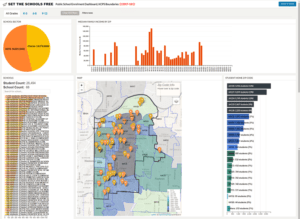

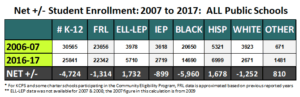

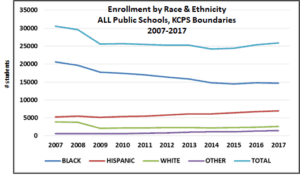

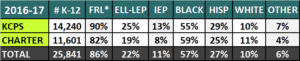

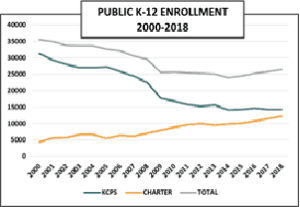

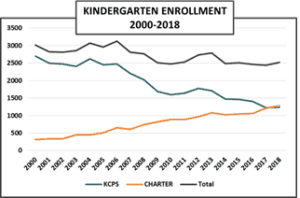

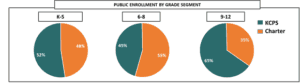

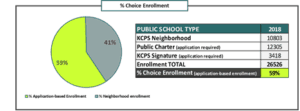

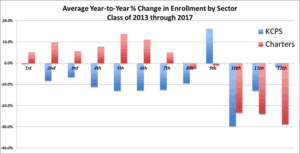

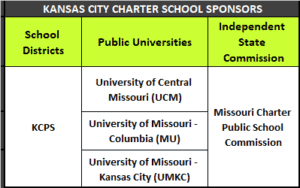

In Kansas City, five sponsors oversee 21 public charter school operators that together educate almost 50% of all public school students. As accountability agents, the role of sponsors is central to realizing the full potential of the charter school model and its promise to improve school quality.

In Kansas City, five sponsors oversee 21 public charter school operators that together educate almost 50% of all public school students. As accountability agents, the role of sponsors is central to realizing the full potential of the charter school model and its promise to improve school quality.

(Note: UMKC recently announced its decision to stop sponsoring schools at the end of the 2018-19 school year.)

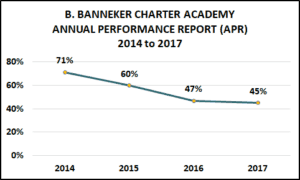

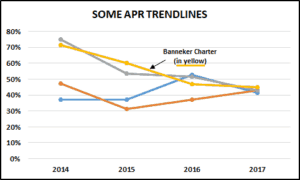

Why close Banneker? Banneker closed because of low academic performance. Annual Performance Report (APR) scores and other assessments were on a steady downward trend. Teacher and student retention were low. The school hadn’t made progress on its remedial plan.

So when its five-year contract was up for renewal, Banneker’s sponsor, the University of Central Missouri, voted in October 2017 not to renew the school’s sponsorship. You can see the UCM press release here.

Banneker’s board fought UCM’s decision and tried to find another sponsor. School leaders told parents the school would continue to be open. And legal action taken by the school – still ongoing – complicated efforts to help families looking for new school options. The result was uncertainty and confusion for students, families and staff. When Banneker finally closed on June 30, 2018, the headlines were mostly about families scrambling to find new schools.

What can we learn from Banneker’s closure? As our charter sector grows, and KCPS considers moving more intentionally into sponsorship, it’s important to take stock of the big picture. Here are three key take-aways:

#1: Autonomy for accountability – when supported by objective data, high expectations, and a willingness to make hard choices – works. The whole point of charters is to provide families with more quality school options. Autonomy for accountability – the idea that if a school isn’t performing, it should close – is the beating heart of the charter school model.

When this model is supported by objective data, a belief that all students can achieve at high levels, and a willingness to make hard choices, it works.

Banneker’s closure shows us that there is a framework and process in place for regularly evaluating and, if necessary, closing public schools based on performance. It’s called the charter renewal process and, in Missouri, it happens every five to ten years (contract duration is based on historical performance).

The renewal process takes into account a variety of comprehensive trend data related to school governance, academics and finances – and measures that performance against the expectations laid out in the school’s charter. Decisions for renewal, non-renewal, or closure are based on evaluation of these data.

Is the process perfect? No. Is charter school accountability in Kansas City uneven, does it need to be strengthened? Yes. But the fundamental premise of the model is sound. Banneker’s closure is proof that autonomy for accountability can work.

#2: School-level accountability shouldn’t just be for charter schools. The idea of school-level accountability – that schools should be evaluated on their individual performance, and that failing schools shouldn’t operate in perpetuity – is another important contribution of public school chartering.

But if you believe that under-performing charters are harmful to the students they serve, then you have to ask: Why is it OK for failing traditional public schools to operate indefinitely?

Because school quality isn’t just a charter problem.

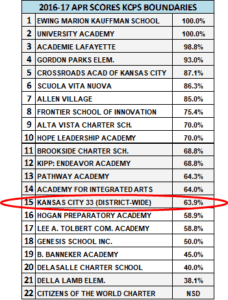

KCPS recently announced its interest in sponsoring more charter schools (the district currently sponsors one charter school, the Kansas City Neighborhood Academy). It’s an intriguing idea but merits the question: can you be an effective charter sponsor if you’re unwilling to apply the same accountability principles to your own schools?

(It’s important to remember that there are alternatives to neighborhood school closure. A number of districts – like Atlanta Public Schools, which I wrote about in September – are coming up with innovative ways to bring together the best of both charter and traditional public schools in a neighborhood context. These models hold promise, and are worth our attention.)

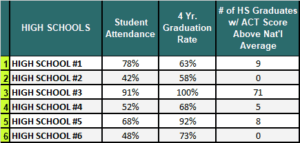

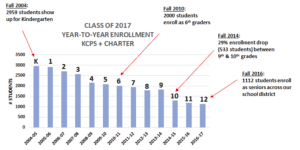

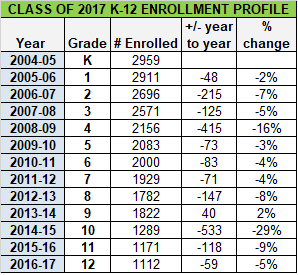

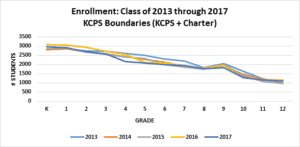

#3: We need more visibility into school performance. As I tried to understand Banneker’s closure and put it in context with the performance of other public schools, this was probably my biggest take-away: we need more visibility into public school performance, both at the individual school level and in aggregate.

Because it’s really hard to have a thoughtful conversation about schools, or about school quality, when you don’t have access to meaningful information – or when the information you do have is conflicting.

Let’s be honest – school performance, for most of us, is a big mystery. There’s a lot of data on DESE’s website, yes. APR scores are helpful. But most of us don’t have access to sophisticated data analysis. We have no idea how individual schools perform, how absolute scores differ from student growth, how performance data looks over time – or whether or not it’s even appropriate to compare one school’s performance to another, given the population of students they serve.

We need to figure out a way to make school performance data more easily accessible and understandable – for parents, for schools, and for the broader Kansas City community.

Far from being a threat, creating a culture of openness around school data would actually make it a lot easier to problem-solve, to help schools improve, and to learn from our mistakes. It would also protect the interests of school board members (both KCPS and charter), school leaders, and charter school sponsors who are tasked with making hard decisions that affect students and families.

And it would go a long way in helping to both inform and normalize the conversation on school quality in Kansas City – a topic we should be talking more about.

__________________

These are my biggest take-aways from Banneker’s closure. What are yours? Feel free to leave a comment below.