So, where were we?!!

Welcome back to Set the Schools Free. In my last post, I argued that the steady growth of Kansas City’s public charter school sector is telling us something important – if we’re willing to listen. Now let’s explore what it’s saying.

But first, a quick recap because, well…it’s been a while!

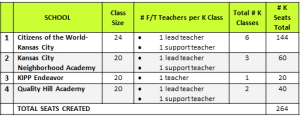

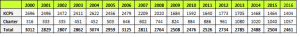

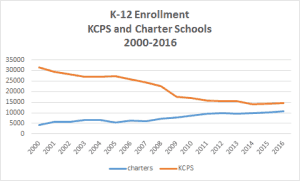

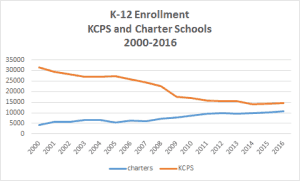

Over the past decade our K-12 charter school enrollment has grown while KCPS enrollment has decreased significantly. Over 40% of public school students within KCPS district boundaries now attend charter schools – one of the highest percentages of charter market share in the country.

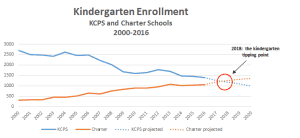

Charter school kindergarten enrollment – a leading indicator for the sector’s growth, and for our public school system overall – is on track to surpass KCPS kindergarten enrollment in the next few years.

The overall growth in charter enrollment has continued despite the sector’s historically weak academic record, and it’s changing our public education landscape pretty dramatically – for better and, yes, in some ways, for worse.

So, what is this growth really telling us? Three big things, I think.

It’s telling us that parents want public school choice (or, at the very least, that they want alternatives to the status quo).

It’s telling us that there’s something about the charter school model of organizing and operating schools that appeals to families.

And, finally, growth in charter school enrollment is telling us that if we really want KCPS to survive, we need to encourage it to innovate and evolve beyond its current, centralized organizational model. We need a new approach for running our system of public schools.

1. Kansas City parents want public school choice.

We live in a school choice system – parents living within KCPS school boundaries have a lot of different K-12 public school options to choose from.

How do we know parents want choice?

Because when they’re offered choices, they take them.

Enrollment data provides the most compelling evidence – it shows where parents send their kids to school. Four of every 10 children attending public schools within KCPS boundaries are now enrolled in public charter schools that operate outside the KCPS system.

If you include KCPS signature schools in the mix – and of course signature schools aren’t charter schools, but they are in fact schools of choice run by KCPS – this number increases to roughly six of every 10 students (3,860 students were enrolled in KCPS signature schools in 2015-2016).

Whether you understand these data as a straight endorsement of school choice, or as an indictment of KCPS neighborhood schools, the results are the same: Six of 10 public school students within our school district boundaries attend public schools that are not their regular neighborhood schools, or are otherwise determined by their zip code.

Parents want choice.

2. There’s something about the charter school model of organizing and operating schools that appeals to parents.

When the parents of more than 10,000 students opt out of our traditional school system and choose charter schools for their children, it’s telling us something important about what families need and want from public education in Kansas City.

Kansas City’s charter sector is made up of an incredibly varied group of schools. As of the 2016-2017 school year there are 22 charter organizations in Kansas City operating 38 individual schools.

These schools differ greatly with respect to school model, leadership, philosophy, demographics and, yes, academic performance.

So what’s the unifying element of this varied group of schools, the one thing they all have in common?

Local ownership.

Under the charter school model it’s the school leaders – educators who are in the school interacting with teachers, students and parents every day – who are a schools’s key decisionmakers. They’re supported in this decision-making by their governing school boards.

This local ownership is what’s generally referred to as “school-level autonomy” and it means that key decisions affecting students – whether it’s staffing schools, choosing a curriculum, selecting a behavior management system or deciding the length of the school day – are made at the school level, rather than by district-level administrators operating in a central office far away.

You can see how this type of school-level decision-making, stripped of several layers of district bureaucracy, could foster a closer connection between a school and the students it serves and might be appealing to parents who’ve lost confidence in “the system.”

But there are several other benefits to this type of independent, or autonomous, public school model:

It helps protect the interests of individual schools – interests which, for schools operating under the umbrella of a large school system with many competing needs and priorities, can often be ignored or overlooked.

It reduces the distance between parents and schools, a distance that can feel insurmountable – especially for parents who lack the time and resources to navigate a vast school system bureaucracy to advocate for their child.

And it moves us away from the one-size-fits-all model of public education by creating the space for new groups with new ideas and new energy to start their own schools, bringing more families back into the system. It doesn’t assume that any one group has all the answers for how our public schools should be run.

3. If we really want KCPS to survive, we need to encourage it to innovate and evolve beyond its current, centralized organizational model.

There’s something else that our growing charter sector is telling us, if we’re willing to listen: it’s telling us that KCPS has more than a public relations problem. It has an organizational problem. And more specifically, it has a centralization problem.

KCPS is a school system caught between two worlds. It wants to be a competitive player in an increasingly crowded and dynamic K-12 school marketplace.

But it’s saddled with a central planning mentality where many of the most important decisions affecting schools are still made in the Central Office, far from the students and families KCPS serves.

To be fair, this central planning mindset makes sense when you consider that a big reason school systems exist is to promote efficiencies by capitalizing on economies of scale. In a system context, for example, it’s faster and cheaper to choose one curriculum and push it out to 100 elementary schools, than to have 100 schools select and implement 100 different curricula.

This centralized approach to running schools, however, assumes that a small group of administrators knows what’s best for an incredibly varied group of schools and students.

It disempowers school leadership and staff, and creates distance between individual schools and the families and communities they serve (in organizations that are highly centralized, customer service is often poor).

And it prioritizes efficiency and cost savings ahead of student learning and what’s best for individual school communities (which it turns out, in the end, is not so efficient or cost effective after all – losing students is very expensive).

This central planning mindset, and the resulting schools environment it creates, ultimately holds KCPS back as it tries to grow school enrollment.

If we want KCPS to survive, we need to help it innovate and evolve beyond its current, centralized organizational model. We need a new way of thinking about, and a new approach for running, our system of public schools.

___

Thanks to those of you who shared ideas and feedback that helped inform this post!