When we talk about public education in Kansas City, efficiency matters. But the more important conversation is about school quality, and where decisions affecting students are made.

In late 2018 KCPS began sharing an analysis of public education within KCPS boundaries. The Kansas City Public Education System Analysis is a comprehensive study that reviews the current state of public education within KCPS boundaries, along with accompanying trend data.

Set the Schools Free believes that if we can build consensus around an objective set of facts, we can have a different, and more productive, conversation about the future of public education within KCPS boundaries.

By making the District’s understanding of the facts publicly available, and initiating a community conversation about these facts, the KCPS System Analysis makes a significant contribution to this end.

So what does the analysis say?

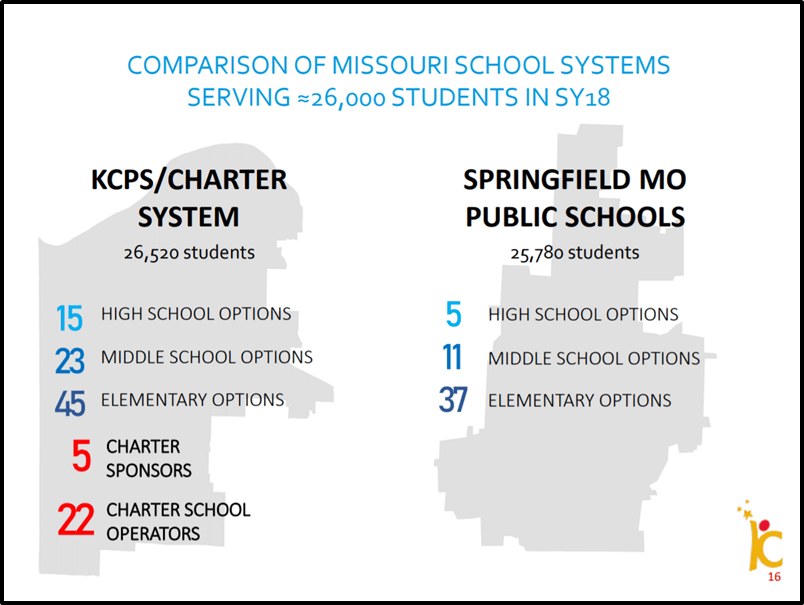

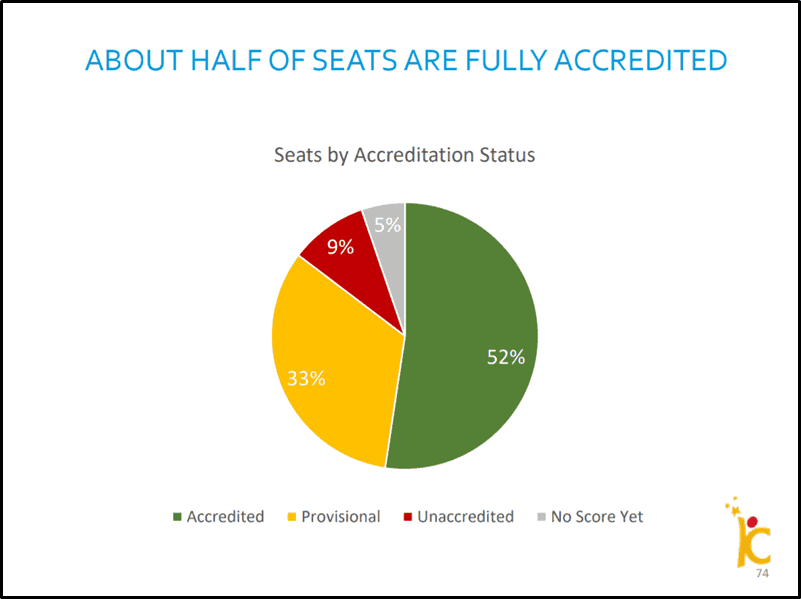

There’s a lot of data, and it can be hard to make sense of it all. In summary, though, we have a lot of schools. Too many are too segregated. And too few are high-performing.

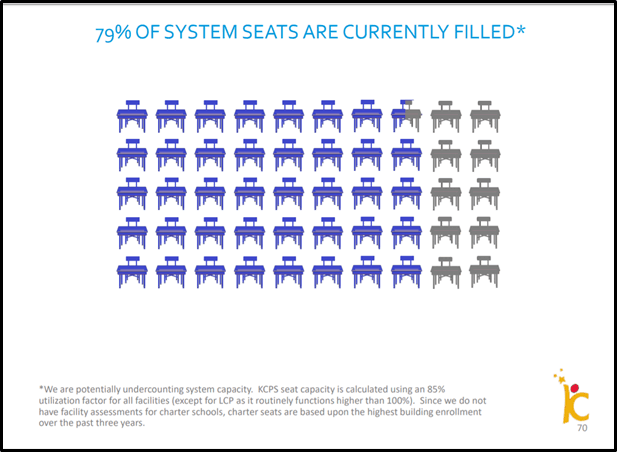

But the story we tell to explain why, in 2019, our district looks the way it does matters as much as the numbers. And the loudest story I’m hearing is one of inefficiency and empty seats created by too many public charter schools.

This inefficiency narrative is problematic for three reasons:

- It misses the point of school choice. Efficiency alone doesn’t lead to better student outcomes. The point of school choice, and public charter schools, is to improve access to quality schools for students who, by virtue of where they live or socioeconomic status, lack quality school options. As long as we have students sitting in chronically low-performing schools, we need new school options.

- It overlooks our traditional school district’s role in the proliferation of choice. Charter schools first opened in 1999 as a response to chronically low-performing KCPS schools. Two decades later, in 2019, there are still chronically low-performing KCPS schools. (And, yes, we now have some low-performing charter schools, too).

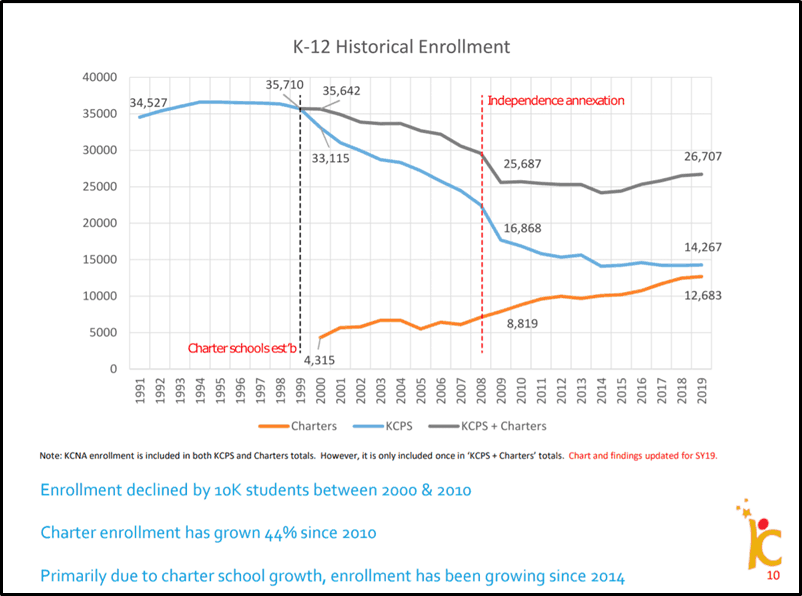

- It ignores what charter growth over the past two decades is actually telling us. At 47% of all K-12 public enrollment, Kansas City has one of the highest charter market shares in the country. Families are voting with their feet, and many are choosing charter schools. Why? Conversations about efficiency don’t help us answer this question – and they don’t help KCPS become more competitive as an operator of public schools.

So what’s the conversation we should be having instead?

It’s a conversation about school quality…

This isn’t an efficiency conversation, or even a district-charter conversation. It’s, first and foremost, a school quality conversation.

25% of students within KCPS boundaries (7500) are in public schools that rank in the bottom five percent in Missouri in reading and math. These seats are in both district and charter schools.

We need to be honest: an open seat in a low-performing, half-empty school – whether KCPS or charter – is probably not a seat most parents want for their child.

So it’s not the decision to start new schools that’s creating too many seats. To the contrary – we have a responsibility to try new approaches and create new school options when quality options are lacking.

Rather, it’s our inability to admit, first, that we have chronically under-performing schools – and, then, our unwillingness to either close them, or initiate school turnarounds -that creates a seat surplus.

A good starting point for kicking off this school quality conversation would be to develop district-charter consensus that low-performing schools – irrespective of school type – should not be allowed to operate indefinitely.

We need to hold all public schools, KCPS + charter, accountable at the school level in a fair, transparent and objective way.

It’s also a conversation about where decisions are made

Growing charter enrollment is driving overall growth in public school enrollment in Kansas City. What are charter schools doing differently and/or better than traditional public schools that may be contributing to the sector’s growth?

Ideology aside, the most important difference between charters and most traditional public schools is where decisions affecting students are made.

In charters, decisions about a school’s most important resources – staffing, budget, time, and curriculum – are made at the school level, closest to students. This is in contrast to a traditional school district where decisionmaking is centralized to maximize efficiencies and economies of scale, which inevitably results in a more “one-size-fits-most” approach to operating schools.

The benefits of school-level decisionmaking

School-level decisionmaking brings a couple of different benefits. It reduces the distance between school leadership and the students and communities they serve, making schools more agile and responsive. It builds a sense of ownership, and encourages different approaches to running schools.

It also helps attract and foster more entrepreneurial talent. And because it’s clearer where decisions are being made, and who’s responsible for those decisions, it helps promote greater accountability. These are all tangible benefits that families experience directly.

If we’re focused solely on efficiency we’re not asking the question: What can our traditional public schools learn from this different model of organizing and operating schools?

Note: Shifting decision-making to the school level does not, on its own, guarantee school success. This is why accountability matters.

Choice is messy – but necessary

Is this school-centered approach the most efficient way to run a system of schools? No, it’s not. But there’s no point to efficiency when it’s not producing the outcomes you want. There’s nothing efficient about schools that lose enrollment year after year, or students who graduate without the skills they need to succeed in life.

The reality is that choice, whether in the public or private marketplace, solves some problems but creates others. It can be messy and time-consuming. And without robust infrastructure to support it, choice can produce inequity, further deepening racial and economic divides. That’s why the work to make Kansas City a more equitable, and accessible, public school marketplace is so urgent.

Do we need more coordination, collaboration and innovation, both between and among KCPS and charter schools, to build trust and maximize dollars going into classroom? Absolutely. But we should be realistic: a choice-based system will never be as cost-efficient as a traditional school system, where one entity – the traditional public school district – operates all public schools, makes all key decisions, and assigns students to schools based on where they live.

Closing thoughts

KCPS and Superintendent Mark Bedell deserve a lot of credit for undertaking a comprehensive systems analysis, and for initiating a community conversation about the future of public education in our district.

But in having this conversation, let’s not lose the forest for the trees. Efficiency is important. But the cost of failing schools is ultimately much higher than any inefficiencies school choice brings with it. Let’s re-focus the conversation on school quality, and on how we can work together to build a system that is more responsive, and accountable, to the students it serves.

An excellent, thought-provoking post! I have the privilege of working with about ten Local Education Agencies in Kansas City to help them identify where students need help and to measure how effective their schools and programs are. There are many, many schools providing wonderful outcomes for students that will help them thrive in their lives and careers. I agree with both of your tenants that sacrificing some system efficiency in return for enabling innovation along with holding schools accountable for their outcomes are appropriate.

You may know that the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education stopped providing Annual Performance Report results at the school level in 2018. I see an ongoing need for a common accountability system at the school level so parents and other stakeholders can make informed decisions about where to send their children.

Keep up the great work!

Thanks, Bruce, for your comment – and for the information about the Annual Performance Report (APR). I knew that the school-level APR score went away in 2018 (though the supporting data is still available for each school on the DESE website), but I’m still not sure why it went away, or whether or not it’s going to come back. I agree that we need some sort of common accountability system at the school level.