With KCPS board elections upcoming, Set the Schools Free wants to shift the focus from KCPS “the system” to KCPS “the schools.” Only 1 of 5 KCPS third-graders reads on grade level. What can the the incoming board do to address this problem?

Last week I attended a Kansas City Public Schools candidate forum hosted by Show Me KC Schools. Issues like Pre-K, tax abatements, good board governance, and community partnerships were discussed. There was excitement about the district’s recent APR score of 82.9. The candidates expressed their support for Dr. Bedell, and the progress KCPS has made under his leadership.

Someone asked what KCPS would do to shut down low-performing charter schools. But, otherwise, there was little talk of KCPS schools or student achievement within KCPS.

Is it the system, or the schools?

We hear a lot about “the system” when we talk about public education in Kansas City. That generally means KCPS, our traditional public school system. With +32 schools educating ~14,300 students, KCPS is the largest operator of public schools in our district.

(For an overview of public education in our district, click here).

Public school systems exist for a reason. They provide coherence, and a means of organizing the important work of educating children. They create efficiencies and economies of scale where they wouldn’t otherwise exist. They develop policies that protect the interests of schools and students, and provide a sense of community and identity.

But “systems” don’t educate students. Schools do. And most of us have no idea how well our individual schools are actually meeting the needs of the students they serve.

Whether you’re a parent, school board member, non-profit leader or policymaker, you can’t fulfill your responsibilities – making informed decisions, asking the right questions, designing thoughtful programs, holding schools accountable, or advocating on students’ behalf – if you don’t understand how well schools are serving students.

So let’s shift the focus to schools

The 82.9% APR tells us that KCPS has finally achieved a certain level of system-level stability. With just a few weeks until the election and only three of seven seats being contested (1, 4, & 5), I don’t actually think there’s much opportunity to influence the debate in a substantive way.

But I do think there’s an opportunity for influencing the new board, when it’s installed in April, to shift the focus from KCPS “the system” to KCPS “the schools.”

This means starting to look beyond system-level metrics and holding the administration accountable for academic performance at the school-level in a meaningful way.

Because, really, a school system can’t be any better than the schools that make it up.

It’s easy to get lost in the data, so I’ve picked a simple yet powerful metric to help focus our attention on school-level performance: third-grade reading proficiency.

Third-grade reading as a focal point

Third grade is “a pivot year,” a year when students transition from “learning to read to reading to learn.” Students who don’t read proficiently by third grade are four times more likely than proficient readers to leave high school without a diploma. For Black and Latino students growing up in poverty who aren’t proficient, this number doubles: they are eight times more likely than their more affluent peers to drop out of high school or not graduate on time.

Third-grade reading proficiency is also predictive of health outcomes and life expectancy. People with low literacy skills are less likely to become employed, make living wages, and enjoy long healthy lives. Increasing the percentage of third graders reading on grade level is a goal of Kansas City Community Health Improvement Plan (CHIP).

For all of these reasons, Mayor James launched the city-wide Turn the Page KC third-grade reading initiative shortly after taking office in 2011.

The main point? Third-grade reading is foundational. Low third-grade literacy effectively puts a ceiling on what our schools are able to achieve academically: those same third-graders who can’t read in third-grade continue onto fourth grade, and then fifth, and sixth…..they don’t magically show up the next year knowing how to read.

It’s in the plan

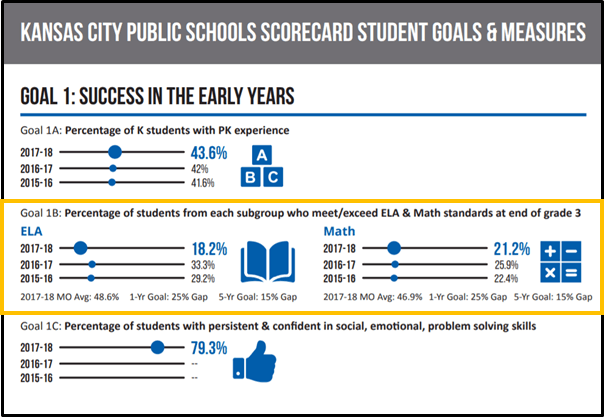

Conveniently, improving third-grade reading proficiency is included in Goal 1 of the 2018-2023 KCPS Strategic Plan.

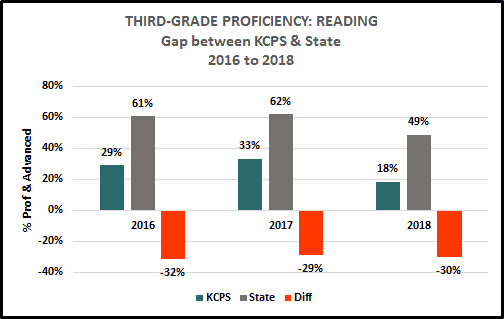

But over the last three years, overall reading proficiency, as measured by the gap between the state average and KCPS proficiency, has remained about the same.

With a 30% gap between KCPS and the state average in 2017-2018, the district missed its first year performance target of 25% for closing the gap with the state by five percentage points.

What does third-grade reading look like across KCPS “the system?”

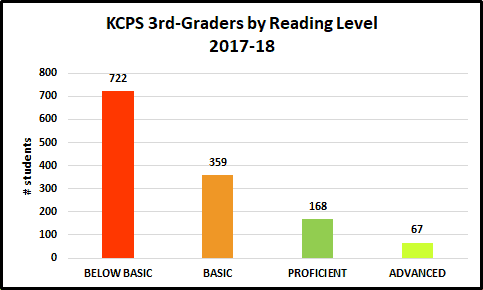

In 2017-18, only 18% of KCPS third-graders – 235 of 1316 students – read at a proficient or advanced level. This is compared to the MO state average of 48.6%.

The majority of third-graders (55%) were Below Basic.

(Note: In 2017-2018, English Language Learners comprised about one-third of all 3rd grade students who took the MAP test. But even accounting for those third-graders, the overall distribution remains the same – the majority of KCPS third-graders read at a Below Basic Level).

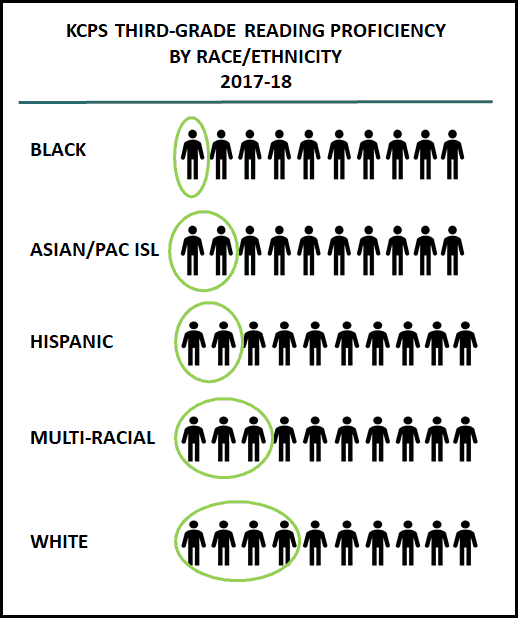

There is a significant disparity in reading proficiency across racial and ethnic groups. Black students make up the majority of KCPS third-graders, 57%, but only 35% of proficient and advanced readers. Only one in 10 black students is proficient or advanced, compared to roughly one in four white students.

Two of 10 Hispanic students are proficient or advanced; Hispanic students make up 26% of all proficient third-grade students. This number is encouraging.

These system-level figures show us we have a problem. But “the system” doesn’t teach students to read, schools do.

What does third-grade reading look like across KCPS “the schools?”

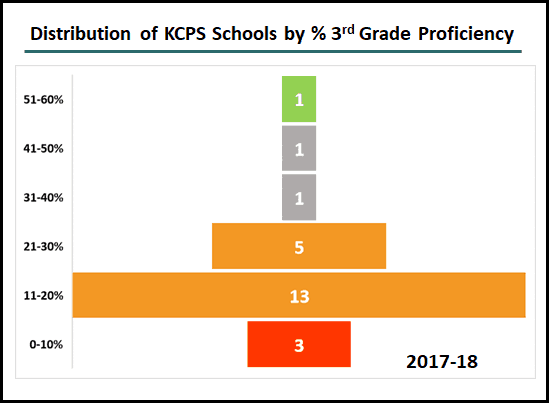

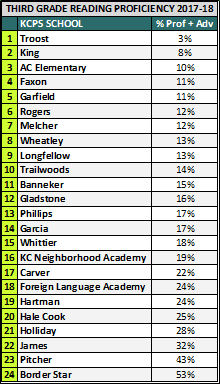

Two-thirds of KCPS elementary schools – 16 of 24 schools – have third-grade reading proficiency rates below 20%.

Proficiency ranges from 3% (Troost Elementary) to 53% (Border Star Elementary, a signature school). For reference, these two schools are 1.5 miles from one another – a five-minute drive by car.

At this point, you might be thinking: “KCPS serves a high poverty student population. Student mobility – the movement of students between schools during the school year – is also high. Of course reading proficiency is low.”

But if we’re not teaching our elementary school students to read, then what are we teaching them?

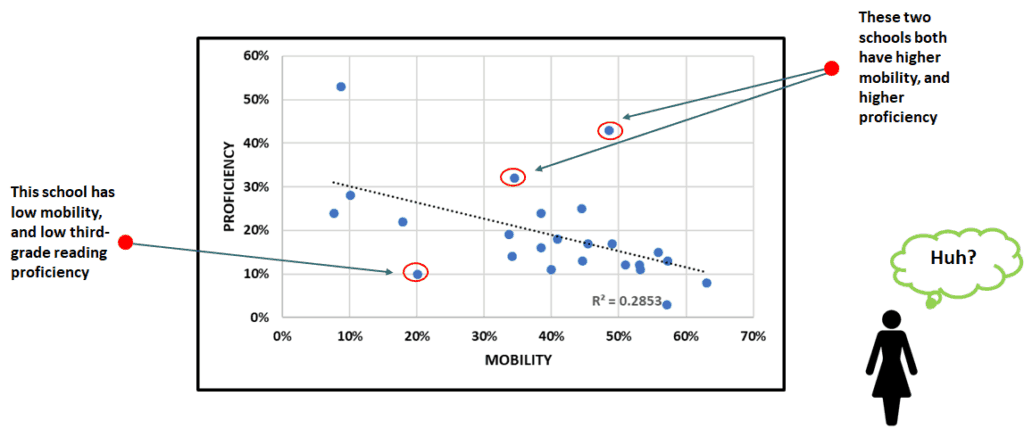

And when you actually look at third-grade reading proficiency next to school mobility data, you see that mobility explains some, but not most, of student proficiency. There’s a significant amount of variation between schools.

The above graph shows that we have schools with low mobility and low proficiency. We also have schools with high mobility, and higher proficiency. One important question: what accounts for the different outcomes at these different schools?

Know the facts – and ask the right questions

So is it the system or the schools?

Both are important. But in the rock, paper, scissors of public education, schools and students beat system every time. We need to shift the focus from “the system” to “the schools.” Third-grade reading proficiency gives us a useful metric to do that.

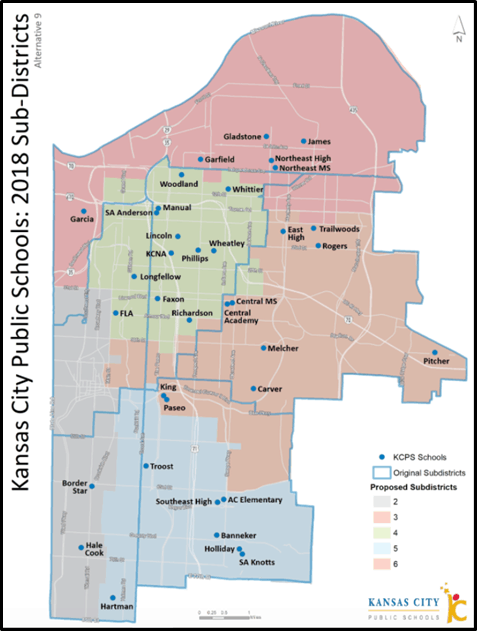

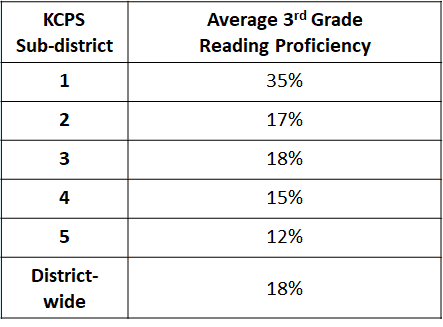

To support the new board in its oversight role, Set the Schools Free has put together a brief powerpoint with key statistics on third-grade literacy in KCPS. To better acquaint candidates and voters with third-grade literacy in their sub-districts, this Primer includes a list of KCPS elementary schools by sub-district, with proficiency percentages and overall sub-district averages.

I’ve also put together a few questions to help kick off the conversation about third-grade reading proficiency:

- What is the district’s third grade K-3 literacy strategy? How does implementation differ from school to school?

- How is reading assessment data used to inform school-level strategy and the allocation of resources across schools?

- What does the allocation of literacy resources across schools actually look like, compared to need? How can we fill the gap?

- Could K-2 classrooms be organized differently to better support early literacy? For example, putting two teachers in the highest-needs classrooms to ensure more individual student support?

- Below basic students make up the majority (55%) of third-grade readers. What happens to these students when they reach the fourth grade?

Set the Schools Free believes that the state of third-grade reading in our school district is important enough to dedicate several KCPS board workshops to this topic.

But at the very least, it’s my hope that, as the final candidate forums wind down and the new KCPS board is seated, board members take this issue to heart.

The new board should request that progress in third-grade reading be incorporated as a standard school-level metric in the monthly superintendent’s report. Just as financial reserves are significant of the district’s overall financial health, progress in third-grade reading is significant of the district’s academic health. There’s a way to do this, I’m sure, that would maintain the urgency around this conversation, keep it meaningful and forward-looking, and prevent it from becoming rote.

And finally, board members can become reading mentors in their local public school (and community members should do this, too!). Visit leadtoreadkc.org and volunteer to spend one lunch hour, once a week, reading with a student.

As a system, KCPS has made significant strides over the last several years.

Enrollment has steadied, and started to grow. Accreditation is on the horizon. There’s increasing momentum around district-charter partnerships. We have a superintendent who has the community’s confidence, and who wants to be held accountable.

Let’s help him help KCPS schools by knowing the facts, and asking the right questions.

___________________________

Note: Because this is a KCPS board election primer, it’s focused exclusively on KCPS and KCPS schools. Set the Schools Free promises to share the same information about third-grade literacy in Kansas City’s charter sector in the next post.